Charles Joseph La Trobe’s appointment as the Superintendent of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales in 1839 was a direct result of his connection to a Christian reform movement which sought to protect the Aboriginal population of Port Phillip.

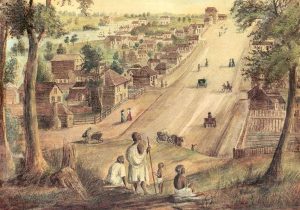

National Library of Australia

In 1837, the British ‘Aborigines Protection Society’ initiated the formation of the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate – a product of a group of like-minded Christian reformers who were endeavouring to avoid the demise of the Aboriginal people of Australia. Lord Glenelg, the Colonial Secretary who appointed La Trobe, noted that one of the most important subjects to which his attention should be directed was ‘the treatment of the Aborigines, and the prevention as far as possible of collisions between them and the Colonists’. But the establishment by the Colonial Office of Aboriginal protectorates in 1838, prior to La Trobe’s posting to Australia, was based on an assumption by the British (shared by many Europeans engaged in colonisation) of the innate superiority of their own culture and that the Indigenous people of Port Phillip could be transformed into citizens of the empire. This displayed a total lack of understanding of Indigenous culture.

La Trobe was sympathetic to the situation of Aboriginal people in Port Phillip. Guided by his strong Christian convictions and a deep sense of duty and justice, he tried to support the Aboriginal peoples through the Protectorate system as he had been instructed to do. While he attempted to protect them by moving them away from the settlers with their alcohol and firearms and their European diseases, he could not control the massacres and murders inflicted in the frontier violence. In July 1840 he wrote to his local superior Governor Gipps in Sydney about the inability to control frontier violence:

I am ready to believe that many acts of aggression, and of subsequent retaliation, have been, and perhaps are completely hidden from the government. I regret to state, that from the experience of the protectors in the character of their duties as magistrates, when called upon to make investigations, and the insurmountable obstacles presenting themselves of obtaining evidence of an available character, it has been hitherto nearly impossible to bring the parties implicated to justice. In scarcely a single instance have the parties implicated in these acts of violence, whether native or European, been brought [to] trial; and in not a single instance has conviction taken place. The more sanguinary the affray, the less were the chances of conviction. Were the murder committed by the blacks, there were no witnesses, or no chance of identifying the parties; and were the natives the sufferers, the settlers and their servants, who were the principals in the first and second degree, were the only person from whom evidence could be obtained.[1]

La Trobe came to realise the follies of the Protectorate system, with its mis-placed aims to civilise Aboriginal people through religion, education and a settled life, under which enormous damage was wrought on the Aboriginal population. With the influx of people in the early 1850s gold rushes and resulting rapid increase in the settler population there was little hope for preserving Aboriginal lands and cultural practices.

[1] Despatch from Governor Sir George Gipps to the Colonial Secretary, Lord John Russell, 26 Sept 1841. Report, 24 July 1840, signed C. J. La Trobe.